O’Keeffe’s Ethereal Artistic Evolution at the MoMA

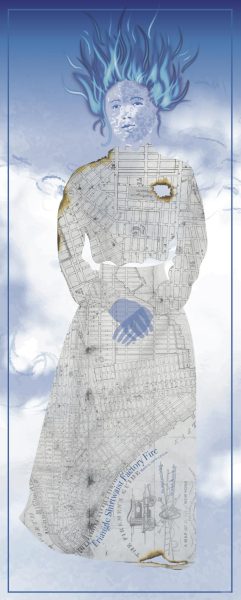

“To See Takes Time” illuminates the genius of O’Keeffe’s method of creation and the genius of her process. (Courtesy of Katriina Fiedler for The Fordham Ram )

According to Georgia O’Keeffe, “To see takes time, like to have a friend takes time.” This gradual process is the inspiration for MoMA’s newest exhibit, highlighting O’Keeffe’s works that were completed on paper. The exhibit, located on MoMA’s third floor, is curated around various groups of work that tell the story of O’Keeffe’s artistic evolution.

O’Keeffe, recognized by many as the “mother of modernism,” is largely known for her large, vibrant and largely abstract paintings of flowers. Moving from New York to New Mexico in 1929, O’Keeffe was heavily inspired by natural forms and flowing shapes. She was the first female artist to be featured in a retrospective exhibit at MoMA in 1946.

This exhibit centers itself around O’Keeffe’s less celebrated and rarely displayed works, many of which are drawn in charcoal and pastel. Although the exhibit is composed of only a few rooms, there are over 120 works featured overall.

The exhibit is organized chronologically, spanning over 50 years of O’Keeffe’s work beginning in 1915. The story begins with some of O’Keeffe’s most abstract drawings, which mark the first developments of her artistic style. In a series of small charcoal prints, O’Keeffe seeks to capture experiences ranging from intense headaches to the sound of music itself. As visitors circle around the room’s exterior wall, they witness her progression towards modernism.

Most striking about “To See Takes Time” is the dedication O’Keeffe gives to each of her subjects, often portraying them six or seven times. One group of such works is of a canyon in Palo Duro, Texas. The first stages of her process are realistic sketches displaying the entire landscape, which evolve into colorful oil paintings consisting only of a few shapes barely resembling a canyon. According to curator Samantha Friedman, “Ultimately, she extracts the key forms that she sees in the landscape, presenting them in a way that seem almost entirely abstract.”

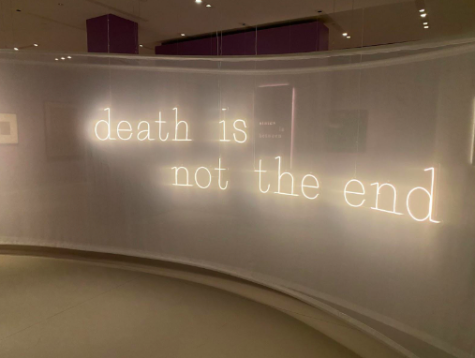

The exhibit ultimately takes its name, and advertising images, from a series of paintings called “Evening Star,” which depict a gradual Texas sunset. Although I found this work less striking, and it didn’t really evoke the sensation of a sunset for me, the bold colors and paint are a fascinating preface to O’Keeffe’s later works, such as the famous flower paintings she is immortalized for.

O’Keeffe’s modernism ultimately comes from her desire to capture sensations and experiences in a visual form. One of my favorite works was titled “Train at Night in the Desert,” which is done both in charcoal and watercolor in various attempts to capture the beauty of smoke at night. O’Keeffe described the sensation of a train pulling in, saying, “A train was coming way o—just a light with a trail of smoke—white—I walked toward it—The sun and the train got to me at the same time— It’s great to see that terrifically alive black thing coming at you in the big frosty stillness— and such wonderful smoke.” Her depictions of experiences that cannot be captured on camera give an ethereal and striking quality to her visual art.

“To See Takes Time” is an exhibit that is certainly worth your time, even if you’re not a fan of modern art. By focusing on O’Keeffe’s method of creation, the curators at MoMA illuminate the genius of her process, as well as her art. Tickets are $14 for students, and the exhibit will remain open at the MoMA through Aug. 12, 2023.

Katriina Fiedler is a sophomore from Atlanta, Ga., who is majoring in economics and urban studies. She first joined the Ram as a contributing writer her...