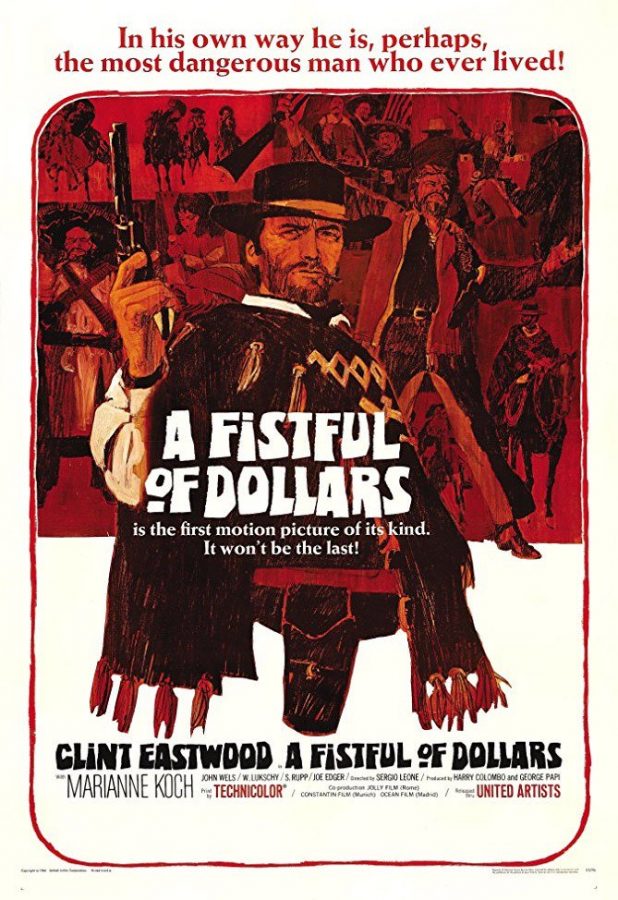

Classic Review: The Western Escapism of “A Fistful of Dollars”

For the first classic film I watched during this period of craziness, I chose “A Fistful of Dollars.” Some may assume that a blockbuster from the ’60s wouldn’t really entertain a modern viewer, even if, for those interested in studying the medium of film, watching it certainly holds value. However, the lean Western is good enough to do both, offering a look at the roots of some of the most heavily used filmmaking techniques in American cinema and enough plain escapism to take viewers’ minds off the sorry state of the world.

For those that don’t know, “A Fistful of Dollars” is the first in what is considered a loosely connected trilogy of films directed by Italian filmmaker Sergio Leone and starring Clint Eastwood, known as both The Dollars Trilogy and The Man With No Name Trilogy.

In “A Fistful of Dollars” and the later two films, “For a Few Dollars More” and the even more iconic “The Good the Bad and the Ugly,” Eastwood plays a gruff but honorable loner cowboy who is so similar in dress and behavior throughout that it’s assumed he’s playing the same character, the titular Man With No Name (even though each film has him at least being called something by other characters, even if there’s not much reason to believe it’s the character’s real name). Collectively, the films contributed greatly to launching both the Spaghetti Western subgenre and Eastwood’s career and are some of the most famous in the global cinema canon.

In “A Fistful of Dollars,” Eastwood’s character is called Joe and after what appears to be a long journey, he arrives in a small Mexican town ruled by rival gangs, the Rojos and the Baxters. Seeing an opportunity to make money and with the advice of local innkeeper Silvanito (José Calvo), Joe works to set the two groups against each other while secretly offering mercenary services to both.

Joe’s shifting allegiances make for a more intricate plot than some other Westerns, but the film’s main focus is still on delivering the kind of spectacle the genre is known for. The most striking technique throughout the film is Leone’s use of close-ups, particularly extreme ones, to build tension, which makes the rapid gunfights that follow even more cathartic. It’s a technique that’s been imitated (and parodied) so often that one might think it has lost its effect, but seeing it used properly in the original context is still thrilling.

Joe’s character development is a relatively standard arc of moving from apathy to heroism, but Eastwood’s iconic performance makes it work supremely well. Ennio Morricone’s swashbuckling score is also of a type that has been heavily imitated, for good reason.

However, the film is certainly a product of its time, and there are some material and choices that might not sit well with modern viewers. Marianne Koch gives a powerful performance with what she’s given, but her role, Marisol, a woman caught in the middle of the gang conflict, is underwritten, with the character being used more as a prop to increase tension between Joe and Rojo leader Ramón (Gian Maria Volonté) than as a fully fleshed-out individual.

Margarita Lonzano is allowed to make a stronger impression as the film’s only other significant female character, Consuela Baxter, wife of the corrupt local sheriff and true leader of the Baxters. Likewise, the ruthlessness of the gang members feels like a stereotypical depiction of Mexicans in this day and age. And while I’d argue that there are points where the film reflects on and even critiques the violence inherent in the Western genre, there are more where it revels in it, even if the actual extent of gore and other brutal imagery is tame by today’s standards.

Still, as far as movies to watch while stuck inside go, one could do a lot worse than “A Fistful of Dollars.” It’s a purely escapist film of a type that doesn’t really exist anymore, and the innovative filmmaking that created it is still striking to watch, as is Clint Eastwood doing what he does best.