76 Years Later, The UN Requires Reforms to Retain Relevancy

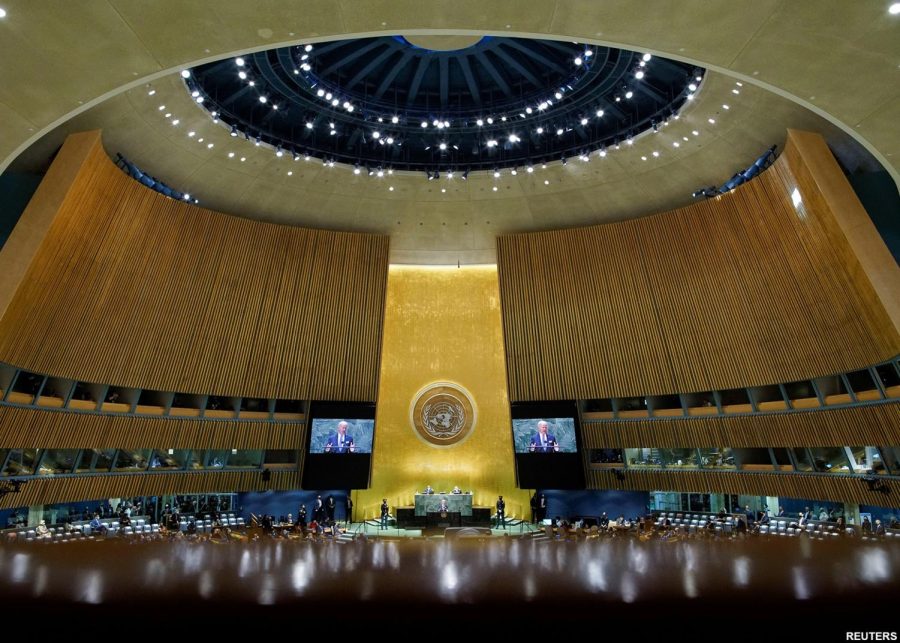

The 76th annual United Nations General Assembly kicked off with a bang this past week in New York City. After last year’s virtual session, diplomats were eager to return in person to the iconic grand hall. Most of the speeches focused on the same issues: climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic and peace and stability in a world that has become increasingly unstable.

It must be a positive sign that our leaders are recognizing the urgent need to address these issues, right?

Not according to Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley of Barbados. “If I used the speech prepared for me to deliver today, it will be a repetition,” she said. “I will not repeat my statements of previous years. Why? Because we have not moved on. We have not moved the needle.”

“We are waiting, waiting for global moral strategic leadership,” Mottley scolded. “How many more crises need to hit before we see that the international system divides, not lifts?”

The unfortunate truth is that Mottley is right. The international system, built by and around the United Nations in 1946, is becoming outdated. Many have been questioning the efficacy of the institution in recent years. Between its apparent inability to prevent or mitigate international crises, from Haiti to Yemen to Venezuela, as well as numerous structural problems, the U.N. needs to shift its focus to institutional reforms and revive its multilateral spirit once more.

We live in a state of anarchy — and no, I’m not talking about the anarchy from movies and books. What I mean is that we live in a world where there is no world government or higher authority. Each state has its own sovereignty and the U.N., as a merely diplomatic institution, must respect this individual power. The U.N. is not a world government, nor should it be, so it makes sense that this is a necessary aspect of its charter. But the document also acknowledges the role that the U.N. plays in “promoting and encouraging respect for human rights.”

So often the U.N. is unable to step in to mitigate crises and deliver aid because of this respect for state sovereignty. In Ethiopia the government is blocking critical supplies from reaching the Tigray region, where civil war broke out late last year. The prime minister is also dismissing 7 U.N. officials from the country after accusing them of “meddling” in the state’s internal affairs. The U.N. is meant to be a forum for diplomacy and a provider of aid, but its authoritative powers are relatively limited beyond that.

Even the few authoritative powers that the U.N. possess internally are outdated and in need of reform. One of the best examples of this is the Security Council. A body of 15 member states, the Security Council is meant to lead the way in addressing crises and threats to peace. But the structure of the U.N.S.C. doesn’t allow this to happen. While 10 members rotate through seats in the council, the P5 — Russia, Britain, France, China and the U.S. — are given extensive powers. These states, many of them notorious for not getting along (I’m looking at you, China and the U.S.), often spend more time squabbling amongst themselves and vetoing resolutions than actually getting things done.

Just take a look at the Security Council’s handling of the war in Syria, the hub of the world’s largest refugee crisis. It took months for the council to renew cross-border aid into the country, and in the end the council approved the renewal of only one of the four checkpoints. In the past decade of war, Russia has vetoed 16 resolutions related to Syria. Too often disputes in the Security Council are more about ideological differences than the actual problems at hand.

The Security Council remains to be one of the more pressing reforms at the U.N. Of the 15 members, the P5 are the only ones with veto power. The other 10 members rotate through two-year terms and are not given nearly as much power. This structure only promotes the hierarchical order of the international system, with the most powerful countries remaining at the top in an institution that is supposed to level the playing field.

Calls for reform in the Security Council have grown louder in recent years. The African Union, whose member states make up the largest membership of the General Assembly, is campaigning to add two permanent African seats to the Security Council. Support for this and other reforms have been echoed by numerous other states and external organizations.

So, it seems like the U.N. has a lot of problems and not enough solutions. But does that mean that this is the end of the U.N.? No.

I had the privilege of interning with the U.N. press corps during the summer of 2020 when the pandemic first hit. I observed and reported on the ways COVID-19 completely upended the U.N. and so many of its operations. I could feel the wariness when the pandemic dragged into its third, fourth and fifth month. At the very least, the pandemic finally revealed the systemic issues and inequalities that persist both in the U.N. and the overarching international order. This did not go unnoticed. It’s why Secretary General Antonio Guiterres’ slogan in recovering from the pandemic is “build back better.”

After the two years that we have all had, I think it is easy to see that things cannot stay the same. Call me an optimist, but there seems to be a noticeable difference in the way issues at the U.N. are being talked about and addressed. Yes, Mottley was right: the needle hasn’t been moved. But this year’s General Assembly came with a renewed sense of urgency that proves this may finally be the U.N.’s time of reckoning.

Allison Lecce, FRCH ’22, is an international studies major from West Chester, N.Y.