“Folk songs were the way I explored the universe, they were pictures and the pictures were worth more than anything I could say.” This quote from Bob Dylan’s memoir encapsulates the nature of “How Many Roads: Bob Dylan and His Changing Times, 1961–1964.” An exhibit that takes you through Dylan’s start in 1960s Greenwich Village, and his incredible trajectory throughout his first three years in New York City.

The exhibit comes from the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which serves as the primary venue for the Bob Dylan Archive. Displayed at New York University’s Gallatin Galleries is a variety of pictures, manuscripts and documentary films, outlining Dylan’s early career and the vibrant folk scene in 1960s Greenwich Village. Mark Davidson, the curator of the exhibit, noted, “The exhibit centers on Dylan’s music as a lens through which to view some of the most defining events of the 20th century.” “How Many Roads” highlights folk music’s impact on the Civil Rights Movement, emphasizing the stories behind “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “The Death of Emmett Till” as well as the correlation with the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on Aug. 28, 1963.

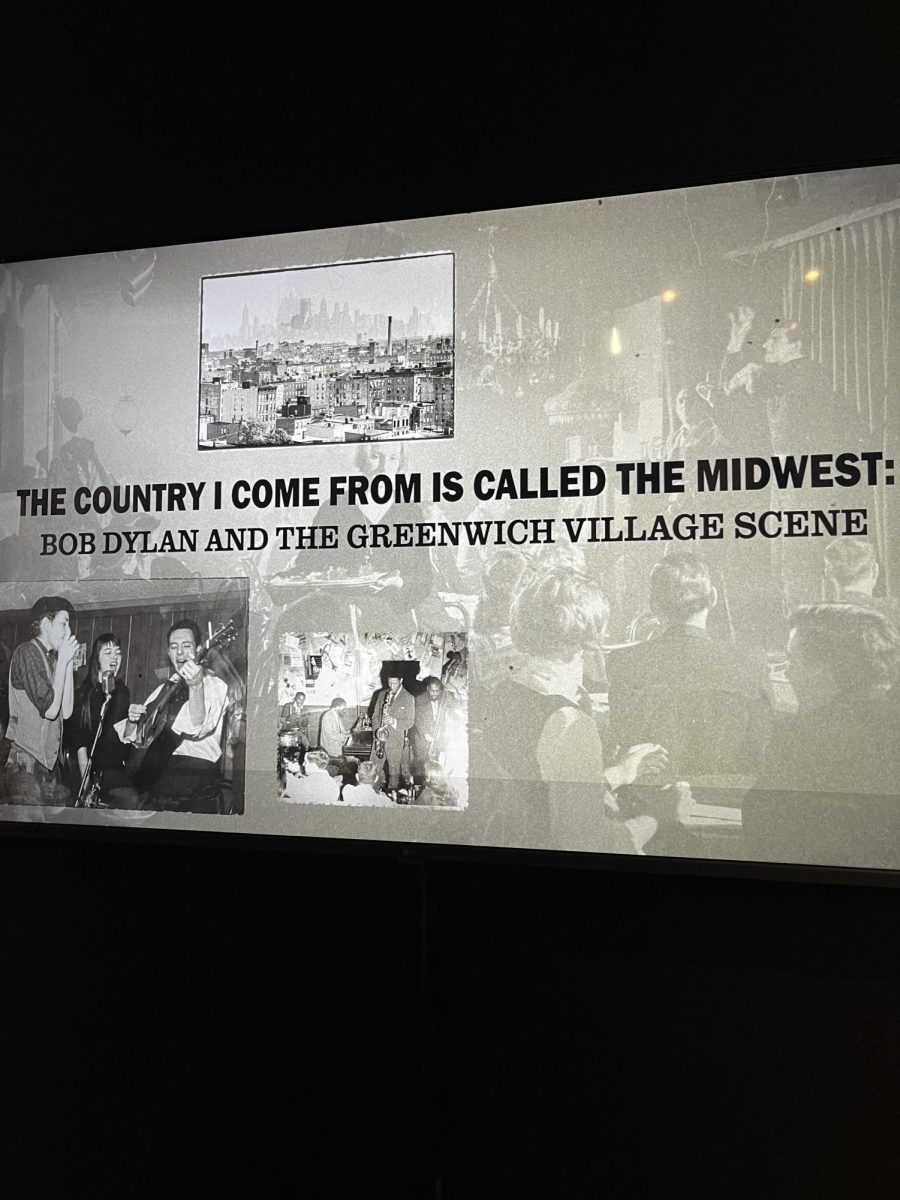

Bob Dylan got to New York City in January of 1961, immediately flocking to Greenwich Village, known for its artistic community of writers, comedians, playwrights and musicians. He began playing anywhere he could find an audience including cafes and clubs like Gerde’s Folk City, Cafe Wha? and the Gaslight Cafe. Here he would meet key Village figures like Dave Van Ronk, Fred Neil and Mark Spoelstra. Later that year, Dylan met his girlfriend Suze Rotolo who introduced him to the city’s cultural and political scenes.

Suze Rotolo worked for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and became a big influence on Dylan’s political consciousness. His musical roots were in traditional blues and folk, but he began experimenting with his lyrics and messages. He wrote his song “The Death of Emmett Till,” a bleak retelling of Till’s murder and the trial that allowed his killers to walk free for a CORE benefit in February of 1962. On a radio show, he explained that the chord progression and melody were modeled after “Bus Driver,” a song by folk singer and civil rights activist Len Chandler. The impact Chandler had on Dylan is not only significant because it influenced one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, but because it illustrates how important music is for awareness.

“Blowin’ in the Wind,” with its vague spirituality and critique against the culture, allowed for it to become an unofficial anthem of the Civil Rights Movement. The song was derived from an African American spiritual called “No More Auction Block,” which expressed suffering, hope and passion. Dylan felt that “Blowing in the Wind” followed the same feeling, but it was particularly powerful because it delivered a powerful, ugly message, in an elegant way. It did not impose opinion, rather it asked questions and allowed the listener to answer those questions. However, it was not Dylan who transformed the song into an anti-war anthem. The folk group, Peter, Paul and Mary, recorded the song in 1963, a year before Dylan released his recording. Their version of the song was decorated with harmonies, calling back to the communal aspect of spirituals, giving the song further nuance and appealing to a wider range of audiences, with the song reaching #2 on the pop charts.

Music had become a major component of the Civil Rights Movement, for its role in inspiring courage and hope, as well as representation in mainstream media. On Aug. 28, 1963, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom drew more than a quarter-million people to Washington D.C. to demand civil and economic rights for African Americans. The March on Washington featured speeches from several civil rights leaders, most notably Martin Luther King Jr., who delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. The march also held performances by several artists like Joan Baez, Odetta, Peter, Paul and Mary and Bob Dylan, whose songs were broadcast nationwide.

Music has the unique ability to transmit messages, critiques, emotions and dreams as well as generate a communal vision or ideology, as it did in the 1960s. The presence of music at the march was therefore vital. The Freedom Singers, Pete Seeger, Peter, Paul and Mary, Joan Baez and Bob Dylan came together for a performance of “Blowing in the Wind,” literally and figuratively emphasizing the importance of coming together for a cause. One year later, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would outlaw discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.

In October of 1963, after just two years in New York City, Dylan sold out Carnegie Hall. He performed his recently completed album “The Times they are A’Changin’” to some 3,000 people. Suze Rotolo is quoted saying, “During the concert, the audience hung on every word Bob spoke and sang and when it was over they gave him a raucous standing ovation. Backstage with Albert Grossman, Dave Van Ronk, Terri Thai and others, I watched and absorbed what was happening. We all sensed a sea of change and it was exhilarating.” “How Many Roads: Bob Dylan and His Changing Times, 1961-1964” captures how music, politics and art came together to shape a generation. Dylan’s songs captured his observations of a country in flux and became anthems for justice. His early years in Greenwich Village speaks to the power of music, not only in melody, but in ability to question, unite and inspire change.