Drill Rap Explores Violence and Identity With a Global Audience

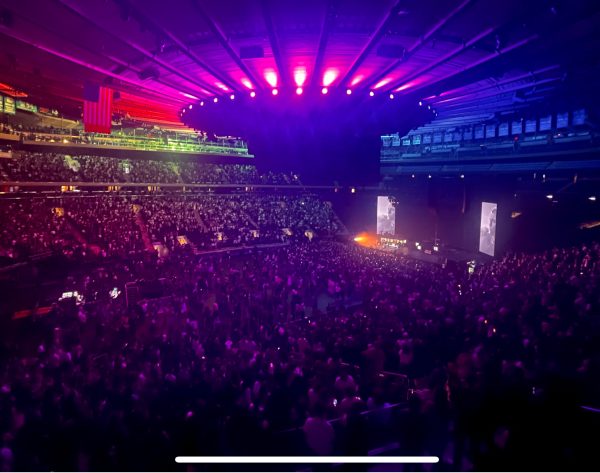

Drill has travelled from its birthplace in Chicago to across the globe. (Courtesy of Twitter)

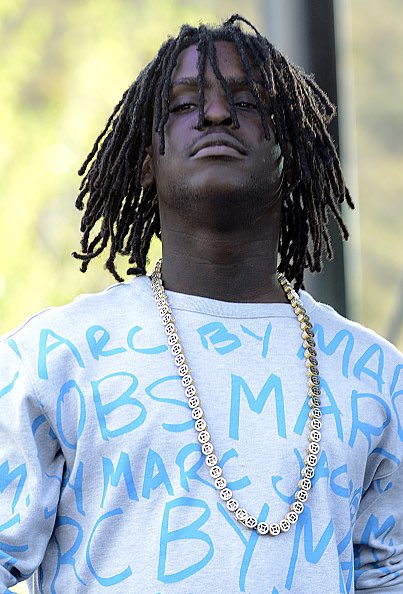

It’s 2011 on the South Side of Chicago, and 16-year-old Keith Farrelle Cozart is spending 60 days on house arrest for firing a gun in his Washington Park neighborhood. I’m not sure how one might expect a 16-year-old to spend their time while on house arrest for weapon charges, but Cozart was determined to use his time productively.

From the confines of his grandmother’s home, Cozart adopted the moniker “Chief Keef” and released the singles “I Don’t Like,” which essentially kickstarted the drill rap genre. Artists like Chief Keef helped lead the development of the drill scene on the South Side, ultimately catching the attention of Chicago rap legends such as Kanye West, who directed big record labels to start paying attention to local drill rappers.

“Drill,” which is a slang term meaning “to shoot someone,” took inspiration from Southern trap music and other mainstream rap songs of the 2000s but focused itself on the gritty violence that artists such as Chief Keef faced in the city streets. The lyrics are often centered around expressing intensity and raw emotion rather than elaborate wordplay or complex structure. Instead, drill artists use straightforward, tough lyrics to emphasize the brutal realities of gun violence and the turbulence of gang involvement in their neighborhoods.

Drill distinguished itself from trap music through its specific focus on violence and death, as well as through its method of presentation to its audience- the genre became popularized through the use of online streaming sites, such as YouTube, Spotify, Apple Music and Soundcloud. Rappers often leaked short video clips as a preview to a new single or uploaded soundbites to provoke intrigue for upcoming projects. The accessibility of the internet has allowed drill rappers to swiftly and easily share music to the masses, paving the way for an unprecedented rise in the popularity of music streaming services as an artistic medium.

The genre has been criticized for its brutal subject matter, as well as for the actions of prominent drill artists; in 2016, Chicago rapper Famous Dex was reported for abusing his girlfriend, and Clint Massey (aka RondoNumbaNine) was sentenced to 39 years in prison for the first-degree murder of a livery driver. Drill rappers have also tragically fallen victim to the very violence they often explore in their music—the murder of Brooklyn rapper Pop Smoke gripped the mainstream media after the 20-year-old was shot and killed in 2020.

Despite facing criticism for the aggressive and oftentimes tragic lifestyles that drill typically chronicles, it has found audiences and performers alike across the globe. While drill rap first began as a specific sound originating from Chicago’s South Side, the genre has garnered worldwide curiosity and recognition. New drill scenes have arisen everywhere from Brooklyn to the United Kingdom, France and Italy, with domestic and foreign rappers contributing different elements to the sound.

Drill has demonstrated a fascinating ability to connect with its listeners and find prevalent niches in different areas. In particular, the U.K. drill scene has provided artists with a gritty new exploration of music and art that reflects the rough neighborhoods where many of these new rappers grew up. Within this subgenre of drill, artists incorporated changes by drawing influences from not only Chicago rap, but also Afroswing, R&B and even grime, which is a genre in the U.K. of minimal garage music that is typified by rapid beats and an electronic sound with a low bassline. The unique influences of the underground U.K. rap scene contribute compelling, intriguing sounds.

In Chicago, drill is defined mainly by its dark lyricism and emphasis on incorporating violent imagery and subject matter into songs and music videos. However, the sound changes and shifts in different locales and has grown to accumulate distinct elements of these various regions. For example, the U.K. drill scene is identifiable not only by its grime-influenced sound but also by its recognizable clothing styles. UK drill rappers have taken to wearing masks and balaclavas that cover their faces.

Some have explained that the masks provide them with a sense of privacy and protection that prevents them from being identified by police, rival groups, gangs or even family members and employers. Other U.K. rappers state that masks also enable them to take on the persona of a drill artist, as if getting into character, allowing them to explore sides of themselves that they might otherwise feel hesitant to express. Behind a mask, some U.K. drill rappers feel more comfortable embodying a more aggressive, vicious identity that they would not normally personify.

In France, drill rappers have drawn heavy influences from the U.K. scene, as some also have elected to cover their faces behind masks. In both French and U.K. drill, performers describe feelings of frustration and anger at not only gang violence and death but also at the failings of the government to offer support for citizens in urban, inner-city neighborhoods.

In Italy, a similar drill presence has cropped up following the death of Pop Smoke, whose sound was influenced by U.K. rappers. Pop Smoke brought U.K. drill sounds back to Brooklyn, expanding the established scene on Chicago’s South Side to an international audience. Italian drill artists have been directly inspired by Pop Smoke, which demonstrates how these rappers have drawn not only from local cultural references but also from international contributors.

Drill rap has the ability to reach such widespread audiences mainly due to its accessibility and online presence. The internet has enabled artists to rapidly share music and videos, and once uploaded, listeners can easily stream songs in a variety of countries. Although the subject matter and content of drill music can be dark and full of brutality, it is undeniable that it is contributing a vastly new sound and shaping the modern rap scene each day.