Ken Ohara built his career on photographing others. Most famous for his project “ONE,” containing over 500close-up photos of people’s faces, Ohara is known for capturing souls, the souls of ordinary people. For a change of pace, he went through his local phonebook in 1974 and, at random, mailed someone a camera already filled with black-and-white film, along with instructions to capture their life however they saw fit. From there, his camera traveled to a hundred people across America.

Ohara’s exhibit CONTACTS is currently on display in the Whitney Museum of American Art untilFeb. 8, 2026. The exhibit is both a study and a depiction of what humans find important enough to capture, as well as a unique display of a photographer letting go of control. This relinquishment of control for Ohara meant giving up the techniques and rules of modern photography. No more framing or lighting to obsess about, just letting amateurs, average people, take a turn. His purpose is to create a bridge of trust and friendship between each person participating, as well as with himself.

The exhibit takes up the entire third floor, though that’s not a huge feat, considering the museum is among the smallest in New York City. As you enter the exhibit through the glass doors, the room is underwhelming. The photos are displayed in uniform frames across the white walls within contact sheets, hence the name of the exhibit. In contrast, the other floors of the museum are much more abstract, made up of sculptures and colorful walls. The plainness of Ohara’s exhibit, however, narrows the focus of the audience to the people within the photos instead of the art of photography itself.

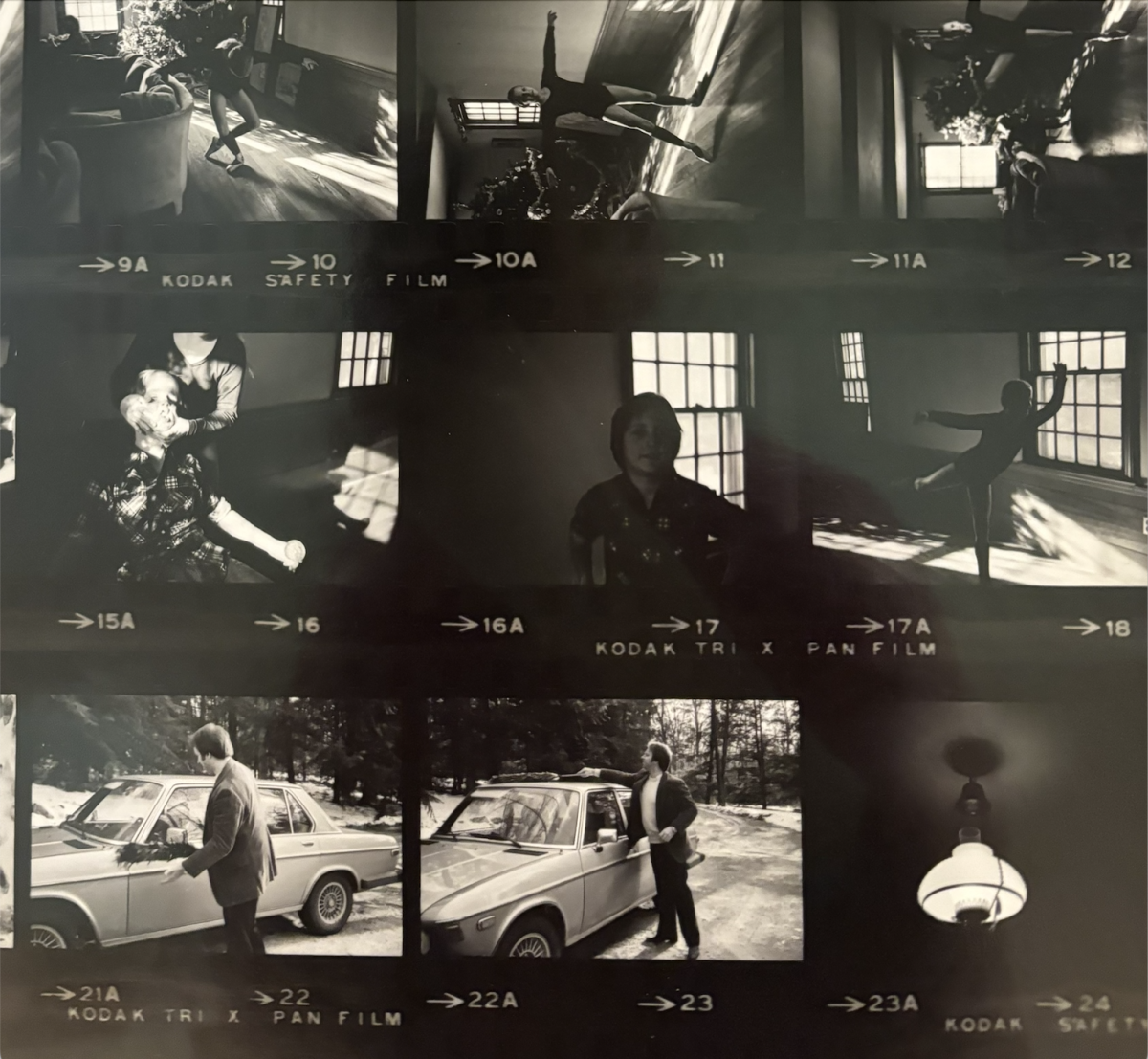

The featured contact sheets are arranged in chronological order along the walls, “telling a story of a distinct moment, place and perspective”. Some frames are completely full, displaying upwards of 36 photos, while others are more empty, displaying only six to 12 photos. Most of the photos are candids of family, friends, nature, cities, homes and animals, taking the artistic route, while others seemed stressed out by the assignment, taking very few, rigid photos. One contact sheet is filled only with eight photos of different people each standing straight up in the same pose, as if someone told them to stay still while they took the photo.

Picture a couple; this contact sheet, absent of color, chronicles a day between a man and a woman. He takes photos of her, slightly blurry, she seems like she’s trying to pose but can’t hold in her laugh. They take some together, selfie-style — before the term selfie was coined — then some of their cat on their couch. The photos are amateur of course, poor framing to the knowing eye, some don’t resemble anything but a blur, but nevertheless were included in the frame by Ohara. Another sheet depicts a family on a dock, a lake behind them with boats floating along the edge of the horizon. The photos radiate a quietness or sereness; you can somehow hear the silence of the family, only the seagulls and the waves making noise.

One contact sheet in particular that is different from the others, depicts photos that aren’t quite as touching. Most of the contact sheet is filled with the same unsettling photos of the same expressionless man. Upon viewing, it begs the question, why do we photograph what we photograph? What do an individual’s photos say about them? Ohara wanted the audience to ponder questions like these, suggesting that photos expose what people value, especially amid the economic crisis and liberation of the 1970s.

Ohara desired to capture “the country’s vastness through the eyes of strangers,” yet chose to include only about 20 contact sheets despite receiving about 100. The specific sheets were meant to tell a story, one that he felt he couldn’t achieve with his own hands. His exhibit is much more than a display of photographs; it’s also a study of what humans value enough to save forever. A camera can act like a telescope into one’s heart, especially when the photographer isn’t trying to create the perfect picture.

The exhibit is, undoubtedly, chock full of nostalgia and the simplistic beauty of normality. The photos emanate a level of humanity, a distinct eye for life that only a human could capture. Such beauty comes only from the amateur level. Though Ohara is a talented photographer, there is a unique viewpoint that comes from the ordinary perspective of Americans. In times of turmoil and division, both in the 1970s and today, Ohara’s “CONTACTS” portrays the vastness of humanity and highlights the portrait of everyday life.