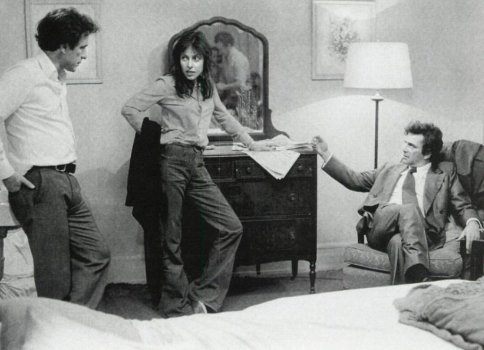

In Praise of an Underrated Director, Elaine May

Elaine May’s work as a director falls under the radar of many film conoisseurs, but her work deserves praise. (Courtesy of Instagram)

In 1961, the comedy duo of Mike Nichols and Elaine May disbanded at the height of their success. Naturally, both members continued their careers in the film industry. Nichols would impress critics and audiences alike with his directorial debut “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” before skyrocketing into the canon of great American filmmakers with his follow up “The Graduate.” In comparison, May’s experience in the film industry was far more troubled, and she’s only directed four features to date. Her final film, 1987’s “Ishtar,” was a critical bomb that many at the time deemed to be the worst movie ever made. Yet I maintain that May is not only an under-appreciated director but also completely deserving of a spot within the pantheon of American film artists. Her oeuvre examines masculinity, politics, relationships and class through a satirical lens, deftly balancing sardonic humor with heartbreaking gravitas.

May’s debut, “A New Leaf,” plays like a macabre screwball comedy: after losing his fortune, a wealthy playboy plots to murder his wife-to-be and collect on her inheritance, a plan complicated by his growing feelings for her. Her follow up, “The Heartbreak Kid,” follows a shallow salesman who cheats on his newlywed wife with a college student on their honeymoon. Bitingly satirical, both films showcase May’s thematic interest in masculinity, featuring self-absorbed male protagonists who don’t get what they want but rather what they deserve. “A New Leaf,” in spite of its grim premise, is a far sweeter movie than one would expect, while “The Heartbreak Kid” is more akin to watching a car crash in slow motion. Her third film, “Mikey and Nicky,” is a gangster picture starring the acting powerhouse of Peter Falk and John Cassavetes as the respective titular characters. After stealing money from a Philadelphia gangster, Nicky calls upon his childhood friend Mikey to help him evade a mob hitman (Ned Beatty). Both of the leads turn in career best performances, with Falk providing a cool and collected counterpoint to Cassavetes’ volatile paranoia. The film showcases May’s singular, actor-centric directorial style. She would often leave the camera running for long after the scene was through, encouraging improvisation among her actors and adding a sense of documentary realism to her films. “Mikey and Nicky” is no exception as May shot well over a million feet of film. Edited down to a mere 106 minutes, the result is an intimate, character driven take on a familiar genre. After a nearly 10 year hiatus from the chair, she would direct her final film, “Ishtar.” What started out as a debt of gratitude to May from producer and star Warren Beatty soon descended into a quagmire marked by both high production costs and tensions among the cast and crew. The film stars Beatty and Dustin Hoffman as two dimwitted musicians who, after accepting a gig in Morocco, find themselves in the crossfire between a leftist militia group and the CIA. The film is not May’s finest, but it’s certainly not one of the worst films ever made, as it is both a razor sharp satire of the Reagan years and a loving ode to male friendships.

Beatty and Hoffman, cast against their respective types as the smooth talker and the innocent dimwit, manage to inject their characters with just enough simplemindedness so as to not become too juvenile, and the film shines in its moments of physical comedy.

Unfortunately, the combination of the exhausting shooting schedule and the ravenous manner in which the critics attacked the film proved to be too much for May, and despite working intermittently in screenwriting and acting, she hasn’t directed another film since.

In spite of her short-lived career, I maintain that Elaine May is one of the greatest filmmakers in the history of American cinema. She was a pioneer of both comedy and cinema, flouting traditional gender roles and defying all expectations of what women in the film industry could be. Part of the reason why the studios never gave her the full support she deserved was that her work deconstructed the very patriarchal foundations upon which the film industry was built. Despite the growing prominence of women’s rights movements during the New Hollywood era, May and her subversive body of work never had the same initial impact as many of her male contemporaries. Thankfully, as evidenced by the Criterion Collection’s 2019 release of “Mikey and Nicky,” there seems to be a shift on the part of cinematic tastemakers towards recognizing May and her efforts. I can only hope that wider appreciation for her work continues to grow, as I strongly believe that her films have aged like fine wine, taking on even greater significance now than they did during the ’70s and ’80s.