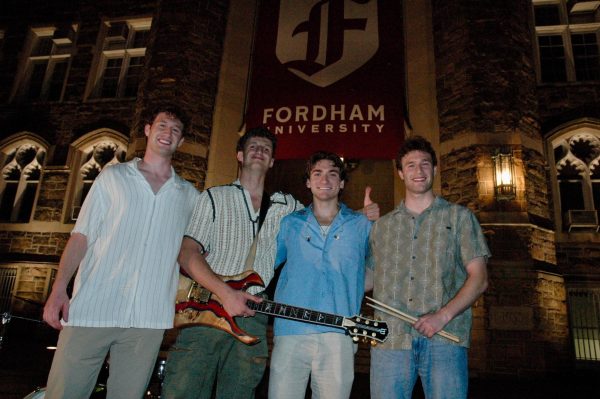

Mahmood Discusses Trust Deficit in Humanitarian Action

On Feb. 6, 2020, Fordham hosted Jemilah Mahmood, M.D., for the third event in the Ireland at Fordham Humanitarian Lecture Series. In her speech, “The Trust Deficit in Humanitarian Action,” she drew on her experience in medicine, humanitarian action and policy to suggest a solution to the problem currently being faced in the sector.

Beginning her career as a physician in Malaysia, Mahmood became increasingly involved in the international humanitarian sector after founding and leading her own non-profit, MERCY Malaysia (Medical Relief Society Malaysia), from 1999-2009. She began her mandate as under secretary general for partnerships at the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in 2016.

The night began with opening remarks from Brendan Cahill, executive director of Fordham’s Institute of International Humanitarian Affairs (IIHA), and Martin Gallagher, humanitarian affairs counsellor at the Permanent Mission of Ireland to the United Nations.

Cahill said the partnership exemplifies the “bridge between academia and the humanitarian sector” that the IIHA was created for. The series was launched as the Permanent Mission of Ireland is running for a seat on the UN Security Council and hoping to demonstrate their priorities in reshaping humanitarianism, along with other important topics such as climate change, in the series.

“Ireland’s role is meaningful here — it has been a leader in education for hundreds of years and has been a backbone of UN peacekeeping,” said Cahill. “It brings its own history of hunger and migration in looking at the issues that confront the international community today.”

Gallagher provided background for the lecture, stating that there are currently 170 million people in need of assistance. He noted that access to these communities, particularly in places of conflict, is increasingly limited and, if granted, dangerous.

He explained that as humanitarian crises become more complex, it is essential that empowering local organizations be at the heart of the solution.

After her introduction, Mahmood began with a call to action to help solve one of the biggest threats currently facing humanitarian action. Mahmood said she finds that the best solution to the problem she faces concerning lack of trust is localization. Before delving into this idea, she underlined the problem.

“(Our reality is built upon) common imagined reality that allows us to believe in invisible constructs,” she said.

She marked the Arab Spring as a turning point in trusting these shared stories.

“Public belief in many core aspects of the system is disappearing around the world,” she said. “We see unprecedented doubt in government, in multilateral institutions, in the media, in globalization and trade and even in science.”

For humanitarians, trust is essential between agencies and the governments whose countries they work in. The donors and, more importantly, the host communities are most in need of aid, said Mahmood. Of the many relationships that require trust, she said the most important is the relationship with communities.

Distrust and fear make containing an epidemic even more difficult, said Mahmood. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) Red Cross organized community engagement and accountability programs to address such fears.

“Yes, we listened, but more importantly, we acted,” said Mahmood. “How can we expect the people we serve to trust us if we are not willing to trust them?”

She explained how listening is the foundation of action. Upon hearing that a majority of Myanmar refugees in Bangladesh were selling their aid, many organizations, including the IFRC, implemented cash programs. It provided independence to choose one’s own aid, which has proven much more effective, she said.

Organizations have also empowered communities to have a say in plans, as one indigenous community in Prince Albert Canada called for during a disaster evacuation disagreement with the government.

“Copying and pasting from one plan to another without taking the time up front to engage, like many of our partners, we are trying hard to break out of this pattern,” said Mahmood.

In regard to finances, more organizations are moving to a direct funding relationship with local groups, such as The Act Alliance. Others, like Mercy Corps in Syria, are also providing remote training and support for local partners to serve at capacity, she said.

Despite such progress, Mahmood also acknowledged that these programs are still not perfect, mostly because they are under-supported. A major issue is that most local actors feel that their voices are muted by international actors.

In the face of such adversity, she shared her own story of going local when she founded her own NGO, MERCY Malaysia.

“As an organization born in a multiracial and multi-ethnic country that I come from, our humility, our deep knowledge of culture, our innate ability to easily build relationships with diverse communities, our precious asset and natural ability to listen, understand and learn from the people we aim to support were crucial building blocks to enable us to deliver the best possible assistance for people,” she said.

Mahmood ended her speech with a call for change for the current and future leaders in the field and a powerful reference.

Ritamarie Pepe, FCLC ’22, said she appreciated her call for “trust in order to refocus humanitarian work” for students and actors alike because of how seamlessly Mahmood connected her experience over the years to her policy.

In a Q&A following her lecture, Dr. Mahmood reinforced her message.

“(Going local allows communities) to be their own heroes and international support strengthens and enhances rather than replaces and undermines,” she said.