In William D. Walsh Family Library’s Archives and Special Collections, the past is not a file on a screen.

It has heft and smells faintly of paper and glue. It simultaneously invites caution, curiosity and patience, the way a thousand-year-old book does when a student lifts its cover for the first time.

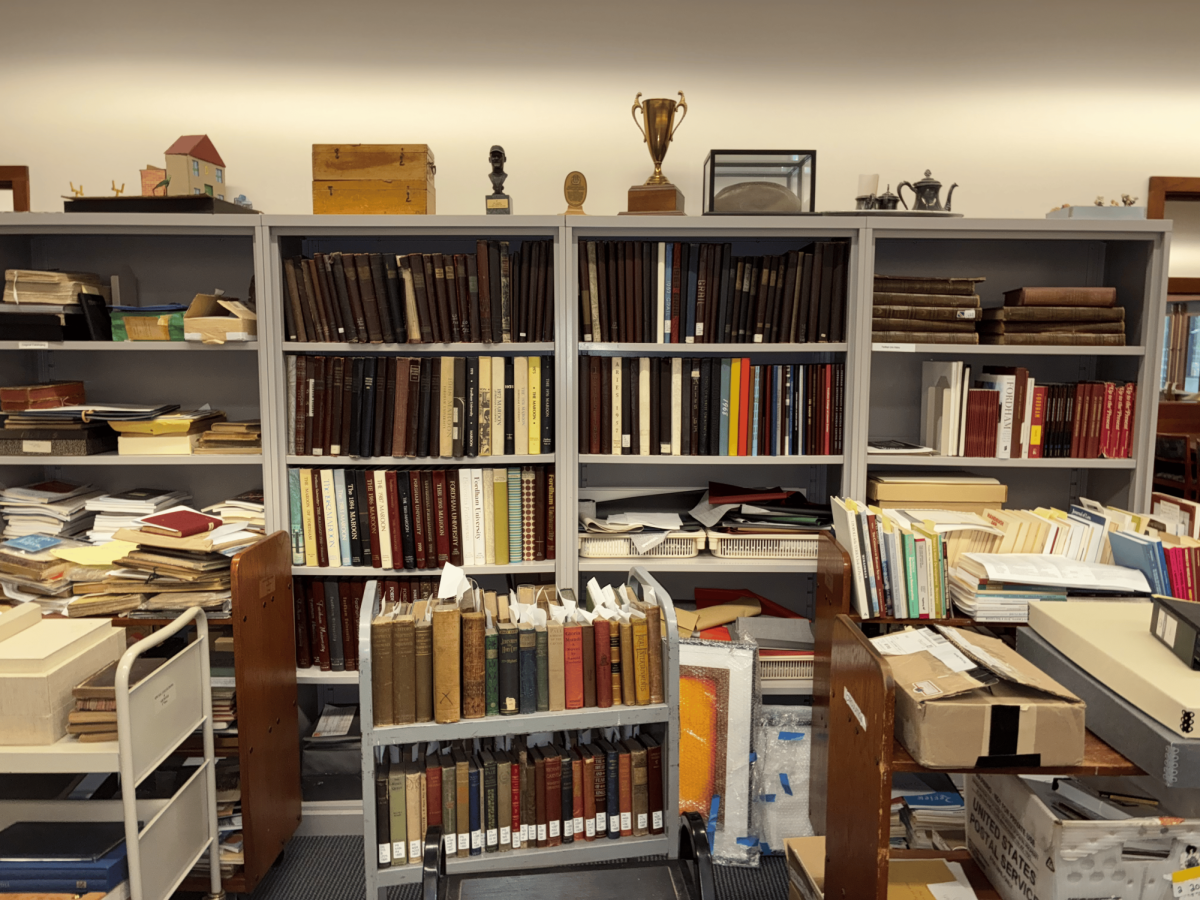

Fordham University’s archive is a working room, not a museum. Faculty schedule visits for classes to come, and the staff lays out the materials they request.

“The biggest users are history classes, medieval studies, some of the classics professors,” said Director of Libraries Linda Loschiavo. The collection runs wide: Rare books, documents, prints, Jesuit literature, even a logbook that includes a July 4, 1776 entry by George Washington, according to Loschiavo. The point, she and her colleagues say, is access with care.

That “care” is real. “It really is more by appointment only,” Loschiavo said, because handling originals takes preparation by a small team. “We have one special collections and archives librarian, and we have one conservation librarian, and that’s it.”

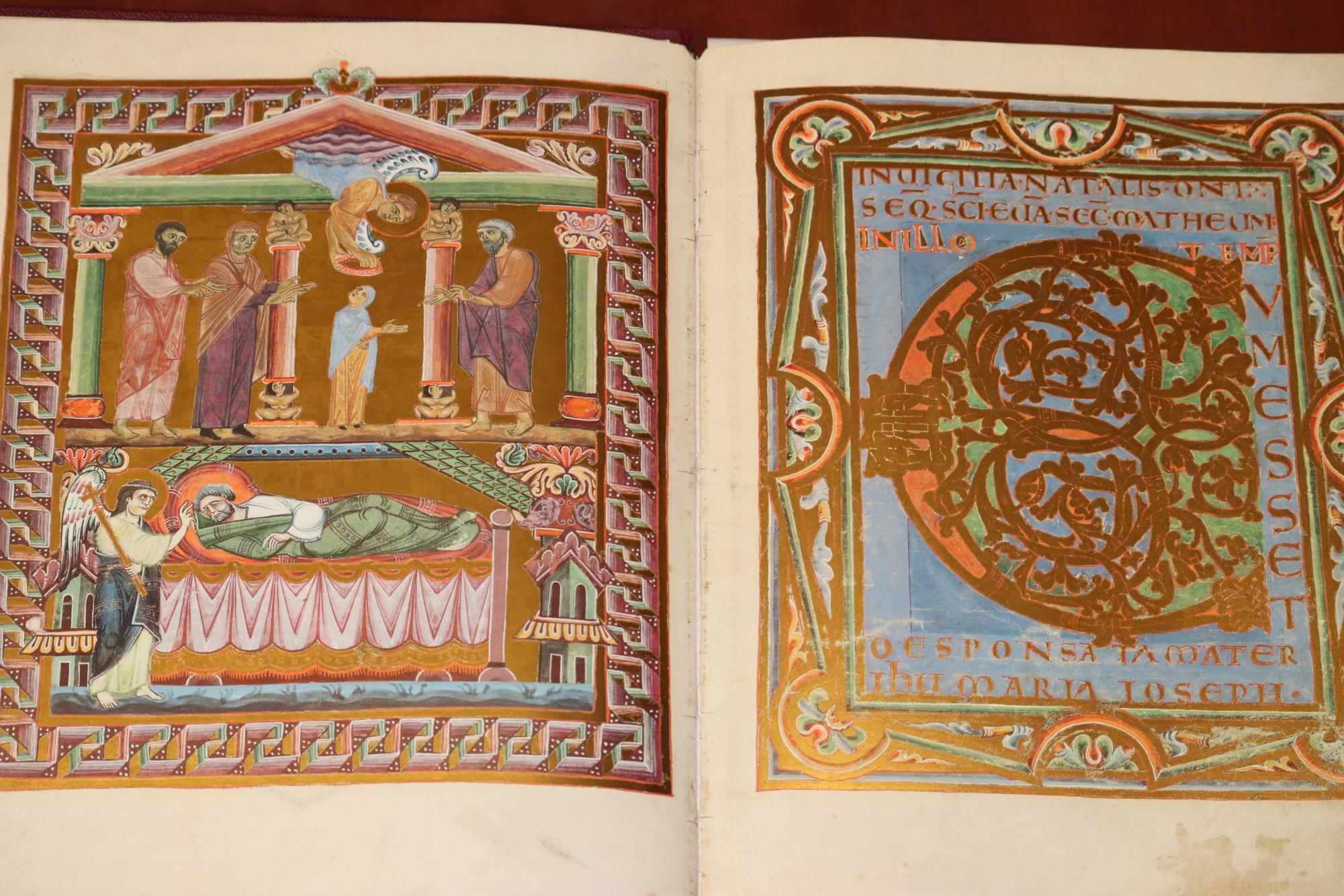

For those in medieval studies, the draw is as practical as it is romantic. “We have an amazing collection of facsimiles, which are high quality copies of medieval manuscripts,” said M. Christina Bruno, associate director of the Center for Medieval Studies. They let undergraduates learn the habits of handling and reading without endangering originals.

There are also differences in physical contact. Bruno calls it “something viscerally really fun … you get to handle something that’s like a thousand years old and it’s actually a little scary.”

For safety purposes, Bruno added, “we watch people very, very closely. We give them a tutorial on how to properly handle manuscripts.” This ability to hold historical items becomes the on-ramp to serious work.

The Special Collections also holds a remarkable set of facsimiles that reproduce every scrape and shimmer from originals held in private libraries and monastic archives. “Everything is absolutely original, except we do have one collection of facsimiles, which a donor has given us,” Loschiavo said. They are art objects in their own right. “One volume of something could easily be $15,000, $20,000.”

For students, that means they can get close to the look and feel of the real thing. “You can get up close and personal and get the experience of what it is to actually go through and handle such material,” said Malena Sullivan, FCRH ’26, who interns in the department and works on conservation and repair.

The work has pushed her toward a career path. “Not every university gets to have such a wonderful collection,” Sullivan said. “I feel really lucky that I get to take a part in preserving some of that.”

Graduate student Lily Carlisle, FCLC ’23, said the easiest wins are simple. Assign a visit. Build it into syllabi. “Writing features on specific holdings in the archive is a pretty good idea,” she added, because stories spark interest. Bruno agrees that the door opens widest when classes go as a group: the staff pulls materials in advance, orients students and watches them handle what they came to see.

The staff’s footprint is small by design and budget, so all visits begin with a request.

Although housed together, the distinction between archives and special collections matters: “Archives” are the university’s own records, minutes, presidential files and catalogs, while “special collections” are the rare books, manuscripts and singular objects. Keeping the two together makes instruction easier, but it also means less shelf space.

The argument for resources is really an argument for the kind of education Fordham says it offers. “You’re never going to read a book … that doesn’t thank the archivists,” said history professor Christopher Dietrich. “The work that they do to preserve the past so that the rest of us have a chance to interpret it is really, really critical.”

In his classes, students learn from the “raw materials” of history: letters, reports, photographs and the justifications Fordham has used over decades for whom it honors.

The archives also hold institutional memory that runs deeper than the current campus conversation. Michael Wares, FCRH ’69, started at the library in 1971 and stayed for 54 years. “In 1971, I took what I assumed would be a temporary job at the library, and liked it,” he said. Wares returned for the first time last week to visit after retiring.

The conservation table has foam cradles, soft pencils and careful hands. It looks like a conservation triage. Sullivan described it as “almost like being in a hospital and figuring out what treatment each patient or each book needs,” from custom boxes that keep spines visible to in-house repairs on circulating volumes.

History professor Daniel Soyer said the great thing about primary sources is that they connect directly to lived experience. For many students, he added, “it’s really exciting to be in the actual archives and to hold in your hand pieces of paper that people wrote a hundred years ago.”

If the archives sound like a quiet place, it’s because they are. But they are busy-quiet. When asked what would help most, students and faculty land on the same two needs: more outreach and a little more room.

The shelves keep filling, and the past keeps growing. Even in the digital age, paper takes space.