People and Planet Over Profit — the Patagonia Way

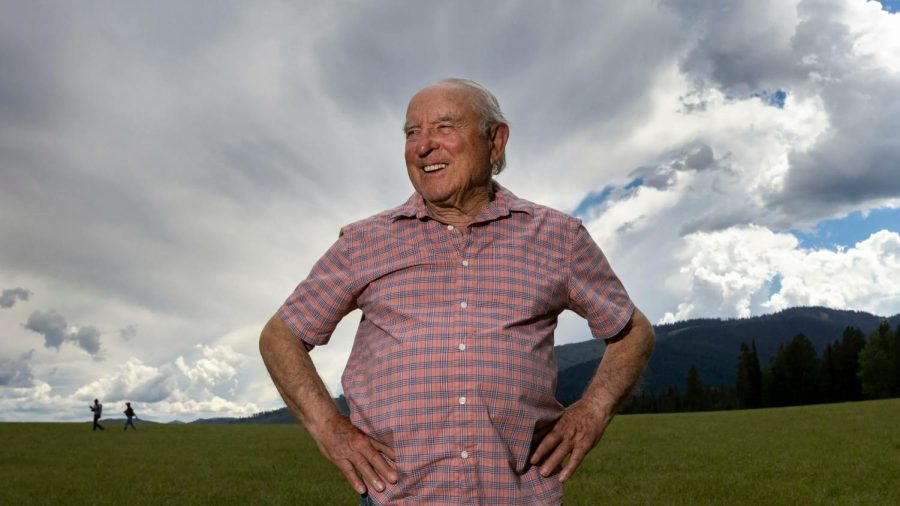

The founder and owner of Patagonia, Yvon Chouinard, has given up his billionaire status and is funneling all revenue from his company into a nonprofit dedicated to fighting climate change. Chouinard wrote a letter to customers explaining this decision with the headline “Earth is now our only shareholder.” Such a claim can bring out the natural skepticism of consumers, many of whom are desperately trying to navigate the intentionally murky waters of ethical consumption. Is this yet another sneaky attempt to market capitalism and the extreme consumer culture of America as a positive thing? Although Chouinard’s intentions are well founded, I don’t think it will initiate a move towards this approach by billionaires in the long term.

“Despite its immensity, the Earth’s resources are not infinite, and it’s clear we’ve exceeded its limits. But it’s also resilient. We can save our planet if we commit to it,” said Chouinard. Transitioning to this precedent-setting business model is Chouinard’s attempt to ensure that Patagonia’s mission and values remain the top priority, regardless of who is in charge. This new approach to billionaire philanthropy is an unconventional move from Patagonia, forcing for-profit companies to reevaluate how they can remain relevant to an increasingly socially-conscious demographic of consumers.

The precedent Patagonia has set will certainly spark a larger conversation about other companies’ responses to the climate crisis. This restructuring will make it more difficult for companies to hide behind an ambiguous model of social responsibility; progress can be made if company leaders are willing to let go of some of their wealth and redistribute it towards a greater purpose.

Chouinard went through many possibilities for a new business model, trying to find a happy medium between remaining profitable and sustained giving. Chouinard has been vocal about his discomfort with his “billionaire” status. “I didn’t want to be a businessman. Now I could die tomorrow and the company is going to continue doing the right thing for the next 50 years, and I don’t have to be around,” explained Chouinard.

The New York Times classified the founder as “an outsider who abhors excessive wealth” as Chouinard uncomfortably described his financial gains as Patagonia grew in popularity over the last five decades. The company has grown to be one of the most recognized for its commitment to its employees, its partners and its customers. Chouinard is not interested in Patagonia conforming to be like its competitors and has remained steadfast in building a company that is led by its values first and its profits second. In a way, Patagonia is an extension of Chouinard himself and his values.

Ownership of the new company will be split between the Patagonia Purpose Trust and the Holdfast Collective. The Patagonia Purpose Trust will protect and promote the company’s mission by owning the voting stock of the company. The Holdfast Collective will “use every dollar received to fight the environmental crisis, protect nature and biodiversity and support thriving communities.” 98% of the company’s profits will be used to ensure that “Patagonia makes good on its commitment to run a socially responsible business and give away its profits,” something that has never been a priority in federal legislation. With the birth of the Collective, Patagonia now has the non-profit status to be able to participate in political activism, in addition to advocating for social justice issues independently. All funding for both of these organizations will come from Patagonia.

Patagonia is a company that has consistently wrestled with its contributions to excessive consumption, an issue that seems to only accelerate every year. Patagonia famously had a campaign on Black Friday with the headline called “Don’t Buy This Jacket.” This advertisement was an attempt to encourage conscious spending on one of the busiest shopping days of the year.

The company recognized that this advertisement could be interpreted as hypocritical, explaining that it is more ridiculous to assume that a healthy economy can and needs to be sustained by buying more and more unnecessary goods. While this advertisement meant well, it wasn’t necessarily effective. The advertisement didn’t have much success in stopping people from buying in excess. Yes, the advertisement is compelling and makes people think about the problems with Black Friday and the values of Patagonia.

This candid approach has aided in the company’s ability to have an honest dialogue with their customers about navigating American consumerism. But it’s not like the company closed all of their storefronts on Black Friday; the company simply wanted to start a larger dialogue about our willingness to spend without blinking an eye, not take more impactful action. It was effective in its shock value, giving the company brownie points with its customers for calling out this superficial holiday, but their sales were still very successful, perhaps even more so with the help of that eye-catching advertisement. With the company’s past of focusing on ethical consumption and the recent restructuring of ownership, it prompts the question: How will this change in ownership impact other companies that claim to be just as transparent with customers?

It is no surprise that this type of business model was created before any apparel or fashion sustainability legislation has been passed. Most fashion brands are not acutely interested in sustainability or fair labor practices, with company profits being the main priority. Although there are potential laws and regulations in the works, none are being established by self-made billionaires like Chouinard. Although it is notable that Chouinard and his family have taken an altruistic approach to their fortunes, I doubt that we will see other billionaires donate all of their earnings for the common good. Although New York may have a Fashion Sustainability Act on the horizon, which would hold apparel companies accountable for combating climate change, there needs to be comprehensive legislation enacted within this industry. It is not enough to hope that every billionaire suddenly wants to be rid of their ties to fame and fortune and will prioritize people and planet over profit.

Michela Fahy, FCRH ’23, is an English and humanitarian studies major and Italian minor from Cedar Grove, N.J.