Celebrating the Legacy of Ted Bonanno

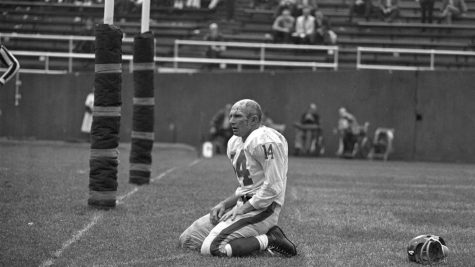

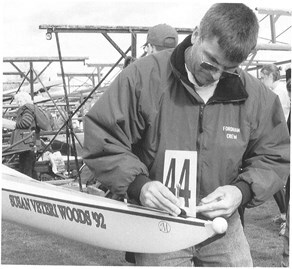

Bonanno has worked with both men’s and women’s rowing teams throughout his coaching tenure. (Courtesy of Fordham Athletics)

Saint Helena’s High School. Its name may be gone — it’s now known as Monsignor Scanlan — but its home in the Bronx remains the same. And it was where Ted Bonanno found his start. A childhood football player came to one of the few high schools in the country without a team. “If they did, I probably would have played football,” he told the Ram. But they did have a rowing program.

It lasted just five years, four of which while Bonanno was there. His homeroom teacher was the team’s moderator. It was this odd coincidence that opened his eyes to the sport, and many more coincidences like that evolved into a nearly 60-year career beginning all the way back in 1962. Now, in 2020, Bonanno announced his retirement after 30 years as head rowing coach at Fordham University.

A five-foot-tall freshman, rowing seemed out of reach for Bonanno, but a sophomore spurt made it feasible. It was a small team, but its connections ran deep. A parishioner at the church associated with the school just happened to be head coach at the New York Athletic Club, and later at Fordham, Hall of Famer Jack Sulger. He brought a rowing team to St. Helena’s, and Bonanno was one of the first to jump aboard.

From there, Bonanno became infatuated with the sport. Rowing both in high school and over the summers at the New York Athletic Club, he grew into “something more than the average high school rower.”

It was there that his career in rowing was jump-started, a small part of a championship-caliber program as a young teenager. The coincidences did not stop. A doubles teammate of Bonanno’s turned out to be one of the very best in the nation and ultimately became a rowing coach as well: first at the U.S. Coast Guard Academy and then at fellow Atlantic-10 school Massachusetts. That level of success right beside him drove Bonanno to do more, and he joined the United States national team.

Success at the international stage, both as a competitor and a coach, led Bonanno to Rutgers University as a lightweight coach. “I enjoyed tremendously coaching there, but it didn’t pay very well at all … and there wasn’t an opportunity to move over into the heavyweight side.” That roadblock brought Bonanno to Columbia, a premier rowing team in the nation’s premier rowing conference, the Ivy League. Just like at Rutgers, it was a struggling program that had not seen a varsity winning season since 1929, but it was the type of challenge Bonanno desired and defined his entire career: taking programs from the ground up and building success.

With that experience behind him, Bonanno wondered where to go next. He stepped away from collegiate coaching for a couple of years, but remembered seeing Fordham practice on the Harlem River at an old Con Edison power plant. Courtesy of another Columbia connection, he had even borrowed one of their boats once in his “first exposure to a university team.”

Fordham was not even a varsity program at the time of his arrival in 1989, one whose boathouse had burned down in the years since Sulger left. “They were barely even able to put a crew on the water, let alone win races,” Bonanno said. But it was the challenge Bonanno embraced, saying, “I wondered if I could go to a program like this and be successful?”

And he was, delivering tremendous outcomes in his first year. He had a nearly perfect season and the sign of a budding powerhouse in the Atlantic-10, owning the competition at the Dad Vail regatta for 20 years in a row, winning 17 national championships and so much more. “I’m sure it was a thrill for the program and alumni that all of a sudden, wow, Fordham is a power,” Bonnano said.

But what stands out most in a career of so much success are the things that are not in the history books, such as the year of denial from the national competition upon introduction to the NCAA. When the team won the Dad Vail, Bonanno called the NCAA to ask for the next steps to qualification. “Are you gonna mail us airline tickets, what’s the procedure? And they immediately told us no, you’re not eligible … you’re a club program,” Bonanno said.

Challenges became a mantra of Bonanno’s career, and the difficulties continued at Fordham. But the rowers overcame them. They “were just tremendously motivated and they wanted desperately to do well, and they would do anything to get the results,” Bonanno said.

Sometimes that meant borrowing a boat from another program, or in the direst of circumstances, rowing out of shipping containers while other programs underwent million-dollar renovations. For Fordham, things were different. Athletes were asked to leave campus at 5:30 a.m., walk across the football field, assemble their boats — rigger, motor and all — and disassemble them when the day was done. “Most college kids are not going to get up at five-thirty in the morning to row, and that’s the easy part!”

And whenever a prospective rower received a call from Bonanno, at the time when there was no recruiting coordinator, neither the challenges nor the team’s status, was much of a recruiting asset. “Quite often, the reply from the high school kid would be, I’m not interested in Fordham,” Bonanno said. “I want to row on a varsity program, not a club.”

The team struggled to even find rowers. Whereas some teams fielded multiple eight boats, Fordham could barely manage one at times. Throughout the ’90s, Bonanno’s men’s team won an eight-boat competition with just nine men, where others picked the best of 40. Many of his best women’s teams were just nine people as well, at times dropping to seven, needing to call up a Hall of Fame volleyball player with just a semester of rowing experience to fill in the spot. In spite of all that, the team won. Over and over again.

When talking to prospects, Bonanno’s answer was always the same. “What schools are you looking at? And they’d mention five or six schools, and often I would say, you know, that’s fine, you want to row on a varsity program, but you mentioned five schools. Just to let you know, we actually competed against those schools every year, and sometimes I could say we haven’t lost a race to any of them in the last five years.”

With his Olympic experience behind him, Bonanno ran his program the same way. He began as a part-time coach, lacking the time to fully devote himself to the team. But when that time did come, he knew exactly what he wanted to do.

“What’s always impressed [me] about the Fordham rowers is how highly motivated and self-motivated they’ve always been, and I decided early on that I was going to treat them like Olympic athletes,” Bonanno said. And the rowers bought into it. “They just took tremendous pride in coming up against some of the best teams in the country and racing them and beating them,” Bonanno said. They may have lacked the facilities or the recognition, but work ethic was the advantage for Fordham.

Fortunately, things have not been so challenging since. Facilities have improved, and the women’s team rose to varsity status. Now, the coaching roster has grown to the biggest in program history along with a squad of perhaps six varsity eight boats, were it not for COVID-19. Yet, the mentality has remained the same.

“Here you have to do the maximum amount of work and get what you want.” Not just as individuals, but as a team. As Bonanno said, “You’re only as good as your weakest link.”

“When you’re in that place and your muscles are starting to burn and your lungs are burning, and you feel like quitting, often what comes to the rower’s mind is I can’t quit,” said Bonanno. “There’s eight other people in the boat depending on me.” It’s an integral part of the sport and of the teams here at Fordham, especially when times were so hard.

For Bonanno, it is not about the championships or the success, but about everything that lay beneath it: developing the rowers, building programs and putting in the work that few others will recognize. And he would not have it any other way.

So what is next for Bonanno? Time away from the sport, or at least that’s the intention. His wife, a New York City school teacher, is set to retire at the end of this year. The two own a beach house at the Jersey Shore and another in Sarasota, both of which Bonanno has not spent nearly enough time in yet.

Originally a pipe dream, the idea of a Jersey Shore house was conjured up to take him away from coaching summers. “So she said, let’s buy a house on the Jersey Shore,” Bonanno said. “And the first thing I told her was like, what are we going to do with a house on the New Jersey shore?”

A promise was made that if the two bought the house, he would take off during the summers. And he did, back at the turn of decade in 2010. It was away from one water and toward another, spending time with friends and family that Bonanno hopes for much more of in the future. “It was just like a big summer vacation, and it was awesome.”

Or maybe he will spend some time with the crystal quartz sand of Sarasota, on a half-moon beach in the Siesta Keys that spans a mile and a half wide. But do not worry, a rowing club is just a few miles away, like how it has always been.

“I’ve enjoyed every single day I’ve been at Fordham … Through all my 30 years here, I’ve always had great support from everyone: the administration, the athletic department, the student-athletes, the alumni, parents. Everyone has been tremendously supportive and I really appreciate and have totally enjoyed all my years at Fordham,” said Bonanno.

Alexander Wolz is a sophomore majoring in communication and culture. He went from writing to assisting and will now be Sports Editing. He also loves video...