Name, Image and Likeness’ Impact on Fordham and College Athletics

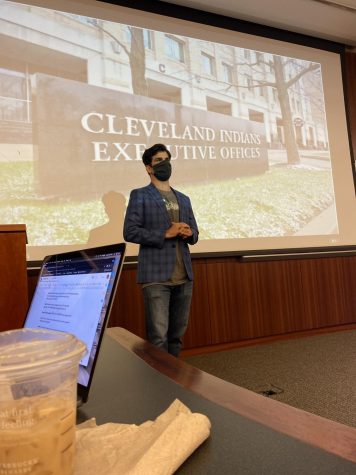

Lust, in addition to serving as a lawyer, acts as a voice within the sports law community. (Courtesy of Linkedin)

College athletics changed forever on July 1, as the NCAA adopted an interim policy that enabled its student-athletes to benefit from their name, image and likeness. The move, years in the making, suspended current restrictions on athlete’s identity, collectively referred to as NIL, amid a flurry of differing state laws as Congress pushes to create a uniform rule guiding the nation’s athletes.

In the meantime, every athlete, regardless of school, conference or state, can now capitalize on their own marketability. Countless athletes are already taking advantage of this, partnering with grassroots organizations in their community or on a much larger scale with national juggernauts like Barstool Sports or even professional teams including the Florida Panthers.

The pure breadth of deals has been quick and sudden, a product of an evolving situation with a very uncertain future, both for athletes and academic institutions. Fordham, right in the thick of this, is and was already prepared for it. That process dates back to July 30, 2020, when Fordham Athletics announced it was partnering with Jeremy Darlow, a renowned brand expert, to help athletes build their own.

At the time, Fordham was the first school in both the Atlantic 10 and the Patriot League to take on such an initiative. Fast forward to January of 2021, Fordham inked another partnership, this time with INFLCR. The five-year agreement was designed to help student-athletes curate their social media brand through access to thousands of media created by the Athletics department to share for their personal use. The A-10 proceeded to announce a multi-year partnership with INFLCR themselves just a few weeks ago, taken one step further to focus on NIL specifically.

Adding one more feather to its cap, both Fordham and the A-10 partnered with Team Altemus and Anomaly as well, describing it as a multi-year partnership consisting of “protective education,” built on both empowering student-athletes and surveying the landscape in front of them.

Collectively, all of these moves position Fordham quite positively within NIL’s early stages. The focus stems from Athletic Director Ed Kull’s previous involvement in the corporate space along with what he describes as the “New York advantage” Fordham possesses. Speaking on the legislative changes on July 20, Kull said, “The Name, Image and Likeness recent rulings and pending landmark legislation are not advancing at a time with any uncertainty in our department.”

However, there is a reason for such programs to exist in the first place: NIL is not so simple. It is a complex juggernaut for student-athletes, administrators and organizations themselves that is only beginning and continually evolving. One person Fordham enlisted to take these educational initiatives one step further is sports attorney Dan Lust of Geragos and Geragos, who recently spoke to Fordham’s men’s basketball team.

To unpack the situation on a national scale, I did the same. In addition to his practice, the Fordham Law alumnus and former president of the Fordham Sports Law Forum previously worked with the New York Giants and currently co-hosts “Conduct Detrimental” with Daniel Wallach, the top podcast in the sports law genre. It is often described as a niche space, but one that Lust has come to dominate as he shared some of his early reactions and advice amid the ongoing developments to the NIL era. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for content and clarity.

The Fordham Ram: When this happened back in July for the first time, to me it was kind of sudden, but I also think it was something we were moving toward for a long time. When the rules first changed, what was your immediate reaction and how have you looked at the fallout of it since in the month that we’ve been here now?

Dan Lust: I had been following the NIL movement since California passed this legislation called “Fair Pay to Play” at the end of 2019. I’ve been watching other states adopt versions of it and I had been watching the NCAA’s response to it. For about a year and a half, the NCAA had some opportunity to prepare for this NIL era and by all indications, their plan was to create a handbook for NIL to apply to any school that didn’t have an applicable state law.

So, for those that were following, just coincidentally in the middle of all of this, a case called NCAA vs. Alston made its way to the Supreme Court of the United States in June. All eyes in the college world turned to the Supreme Court of the United States because they’re saying, ‘Hey, we passed legislation on the one hand, but if a judge comes down and changes our understanding of NIL, this will impact the entire world on July 1.’

So what did the court do there? They ruled in favor of the athletes, which was positive for the NIL movement, but it had some unexpected ramifications. In the decisions, the judges wrote that the NCAA is ‘not above the law.’ So, in response to that, the NCAA seemingly threw it [the guidebook] out and put it in the garbage. They said, ‘if you’re a state that has NIL laws, great. And for the states that don’t have NIL laws, that book that we were going to give you, doesn’t exist anymore, go fend for yourself. Happy Wild Wild West day and we’re off.’

It wasn’t great to do to schools at the 11th hour to tear up what you’d been working on, but that’s what the NCAA did. So that part certainly surprised me that the NCAA certainly left schools high and dry at the last minute.

TFR: You mention how it’s different between the state laws and the federal law and the different elements of it. And then you have the element where so many students have been taking advantage of this from day one and starting to get deals. There’s been some that have had different responses than others. What have you made of, not necessarily the school’s response, but the student’s response to it in the deals they have been pursuing?

DL: I love it. I love seeing [it] to the extent you’re able to. This is what NIL was designed to be. It was designed to be a world where athletes that have a million followers or 100,000 followers, that those guys can cash in. Be it the Trevor Lawrences of the world, the Zion Williamsons of the world. Just that if you can demand an audience and you can demand some money, you’re allowed to do it.

So I think we all understood the high-level athletes are going to do really well, and then all eyes turned to the non-footballs and the non-basketballs. I think what we’ve seen is two-fold: If you have a lot of social media followers and you’re not necessarily going to be the number one overall pick in the draft, you can still make good money.

And then I think below that, if you’re not a star athlete or you’re not at one of these national programs, I think the deals are coming in at a local level. They’re maybe modest in comparison to some of their counterparts, but it’s money coming in the door that you were not allowed to have before.

Interestingly, it’s a little bit of an education on how to hold yourself as a professional. So I think our athletes are learning a lot about the world. They’re not in this little bubble of the NCAA for four years. They have to go out, recruit, hustle. That’s a little bit of the business world they live in. Part of life is going out and meeting people, developing contacts, developing business and our athletes are being asked to do that all of a sudden, which I don’t think necessarily is a bad thing, even if no money comes from it. I think going through the reps could be very helpful.

TFR: Talking about the student perspective, you’ve spoken to Fordham. When you come and talk to these athletes, are you giving them advice on what to look for? Is it more about navigating these laws? What has been your overall message that you’ve been telling student athletes when you speak to them?

DL: It’s a lot of what to watch out for. I tell them the deals, some of the more infamous deals that are occurring across the country just so they can think. I spoke to a lot of athletes. The only schools that I’ve spoken to — Rider, Manhattan, Fordham — all D1 programs, all basketball programs.

I explain, where should you look first in terms of trying to get deals? Alumni and local businesses, one and two. That’s part of my education and I explain to them my different stories of developing business, not necessarily a sports story but kind of have to get those reps in.

But my legal advice is the contracts, the people, the businesses, the clauses in the contract to kind of watch out for. If you’re gonna sign something, which is fine, just make sure you know what you’re signing. You don’t have to necessarily retain a lawyer, I obviously would always recommend having a lawyer look at it, but you don’t want to sign your life away and you don’t want to sign potentially with the brand that’s beneath you and then lock yourself into some exclusivity that would prevent you from going to a brand that is maybe on your appropriate level and would make you more money. So athletes have some leverage, and they just have to learn how to wield it accordingly.

TFR: When it comes to who makes the decisions here, how much of it is a student athlete going to a company and wanting to work with them, and can a school choose whether they cannot or can they have any sort of say in that? Can the NCAA have any say in that? How much of it ultimately comes down to the decision making of just the student-athlete themselves?

DL: If you told me to build the system from scratch, what I would have hoped would have occurred is that the NCAA would clear companies as a whole. I’ve worked for big large law firms; they can clear a vendor and then lower attorneys down the line can work with the company, and you don’t have to go through all this different red tape.

The NCAA has kind of removed itself from the equation. So what I’m hearing is that compliance officers at different schools have to make these decisions on what’s allowed and what’s not allowed in a vacuum. The NCAA is not playing the role of gatekeeper that many expected.

A lot of these NIL rules, and again this is gonna be different in every state and every school, but by and large, the school is not supposed to be involved in the procurement of NIL deals. The athletes, in theory, are supposed to get them. Maybe they have some type of middleman or an agent that helps them secure a deal, but the school is not supposed to be involved with it.

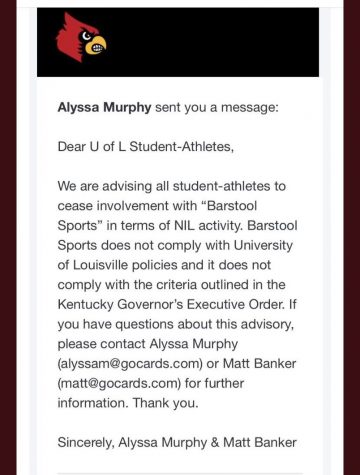

Who gets to decide if an athlete is gonna sign up with Barstool? By and large, it’s the athlete. Whether or not that deal is gonna be allowed or allowed to continue without some form of potential punishment, that remains to be seen. But the initial decision to reach out to a business or to get reached out to by a business, that doesn’t seem to involve the school at all or the NCAA.

So I’ve seen it one of two ways: the business can reach out, the athlete can reach out and then the third one, there’s a handful of these platforms where it’s almost like Tinder. You sign up for a dating site and then the two people can find each other. That’s really the third level of this. I think that third level is where a lot of athletes are finding success. And these platforms, they’ll kind of pseudo-act as a gatekeeper. If you make it onto the platform as a legitimate business, I think athletes have a fair expectation that ‘Hey, this company is okay in my book.’

TFR: You’ve talked a little bit about potentially partnering up with a company that could lock you in, about the compliance element. What of that conversation do you think is the biggest risk in all of this? I can just imagine that compliance has to be a nightmare as certain schools work through this NIL situation.

DL: It’s tough. I think it’s a nightmare for compliance, but I haven’t heard that many deals being shot down. I know I mentioned Barstool, there was another issue with Lululemon but that’s really it. For the most part, schools have not wanted to be in the business of harming the creativity or entrepreneurial spirit of these athletes. So letting a lot of things go for better or for worse.

Compliance people are not lawyers. They’re not designed to be able to look for deals. Their job is not to look through the fine print of the contract and see if this is a good deal for you to sign or not. It’s just to say, ‘Hey, is this entity okay to do business with, is it some type of conflict with our school sponsors?’ For Fordham, right, if you’re a Jesuit school, if the actual brand does something kind of illicit, be it gambling or something with the adult industry, obviously the compliance is gonna flag that.

But when it comes to a company that could potentially lock you to the duration of your college career, they say, ‘Hey, if you post on our platform and you get 50,000 views, we’ll give you $50,000, but short of the $50,000 we’re gonna give you nothing and by the way you can’t sign up with any other [business].’

It’s a complete hypothetical contract, but that’s the issue with exclusivity. If you’re gonna sign up for exclusivity, you gotta make sure you’re getting a ton coming back your way. I’ve seen a couple of deals and exclusivity seems to be an issue with some of them.

TFR: It’s in the infancy of everything here with these policies and as college football seasons come back, I’m sure things are going to keep changing. So what do you think is the picture of this in the short-term, how NIL is going to impact college sports? But also more in the long term, are some of those issues going to start cropping up or is this all gonna just run smoothly over the next few years?

DL: I think there’s one more very big shoe to drop. I went to Fordham for law school, I’m 23. I know what the drinking age is, right, the drinking age is 21. I know that because it doesn’t matter where I went to school, it’s always going to be 21. That’s the national government stepping in and saying ‘this is the drinking age.’ Back in the day, there was a world where the drinking age in some states was 18, it wasn’t 21. It was kind of all over the place, similar to our NIL landscape.

At some point, the federal government stepped in, they said, ‘You know what, this doesn’t make sense. Doesn’t make sense that you could go to a house party across state lines and you have to go home to your state where the drinking age is a little higher.’ It’s not safe, it’s not sensical. Not to say that one state is doing it better than a different state, just make it one rule.

The federal government has convened twice with congressional hearings, I think on June 10 and June 17, to create a federal bill. And in our law, states can do whatever they want absent of federal law on the books in that particular area. So if the federal government passes a federal NIL bill, don’t worry about what Kentucky’s doing, don’t worry about what New York is doing, don’t worry about what Texas is doing, Ohio, California, the federal rule will take precedence.

So I think that’s the future. I keep predicting that it’s gonna happen at some point in 2021. I spoke with people that would be in the know within the past couple of weeks, and the only thing that might change that is a world where the schools turn around and say ‘we actually don’t want a federal bill anymore because we can get away with more stuff.’

I would fear, if I’m a school like Fordham that has some outside influences, being a Jesuit school, that they would have some competitive disadvantage in that particular world. I wouldn’t think that would be fair so a world where there is a federal bill creates a level playing field and cleans up a lot of these weird deals that we’re seeing on a national landscape.

Different schools are gonna have different tolerances, different ethical protocol. And all the credit to Louisville for stepping out and saying, ‘Hey, Barstool doesn’t make sense, why would that be a company that’s allowed under Kentucky’s law. We’re gonna get out ahead of this and say it’s not allowed.’

I know behind the scenes a lot of schools applaud Louisville’s efforts. I hope that they don’t get knocked on a recruiting level because of that standpoint. I think schools are slowly but surely going to start stepping out and enforcing these rules. I think that’s the safest way for athletes. There’s rules in place, someone’s got to adhere to them.

TFR: I remember a year ago now there was such a huge conversation about college athletes getting paid, but now NIL almost seems like a replacement to that. But at the same time, could that be setting that stage for that future you just mentioned, where college athletes are getting paid in addition to NIL and really treated like professional athletes in a lot of ways? Do you think that’s something that could happen?

DL: It’s possible. I don’t want to say that it’s out of nowhere, because in that decision I mentioned, that NCAA vs. Alston case, there was different lines in the judge’s decision that kind of compared college athletes to employees. And employees get health benefits, they get insurance, they get a lot of different things that normally college athletes don’t get.

I think the Supreme Court of the United States obviously is just looking at this objectively, ‘Why are college athletes not viewed as some type of employees when they’re generating so much revenue for the school?’ Is that a world that’s possible? Sure. I think we’re years away from it happening, but if you’re just watching the tides of college spots and you’re trying to predict 5-10 years into the future, I certainly think that’s a conversation that can occur.

And, not to mention, as I am a lawyer I should kind of leave you with this, there’s another case that’s pending right now called House vs. NCAA. And it’s a case basically seeking to expand the definition of NIL to also include piece of television contracts. If people are like, ‘Hey, NIL is great, but I’m a lower level athlete at a big program, I haven’t been able to get a dollar, and it’s not great.’ To the extent you’re at a big program with a television deal, there’s a world where, the court at some point, again in the not-too-distant future, could say, ‘School’s television money actually belongs in part to the players. Every athlete should get some sort of a check here.’

Again, we’re in the Wild Wild West. Sports are kind of coming into put some order into this and help define these terms, but I think these are fair issues to kind of project out. I don’t think either of those, be it student-athletes as maybe being employees at some point or student-athletes being entitled to television or even, as crazy as it sounds, tickets. I don’t think that’s insane. Not to say I’m necessarily in support of it, but I certainly can see it.

Lust also currently teaches as a sports law professor at the New York Law School.

Alexander Wolz is a sophomore majoring in communication and culture. He went from writing to assisting and will now be Sports Editing. He also loves video...